HBM064: A Shrinking Shadow

/Erin was fat as a kid. Since middle school, she tried all different methods to lose weight. From a young age she developed the idea that the most important thing she could do with her life was lose weight.

Note: Explicit Content

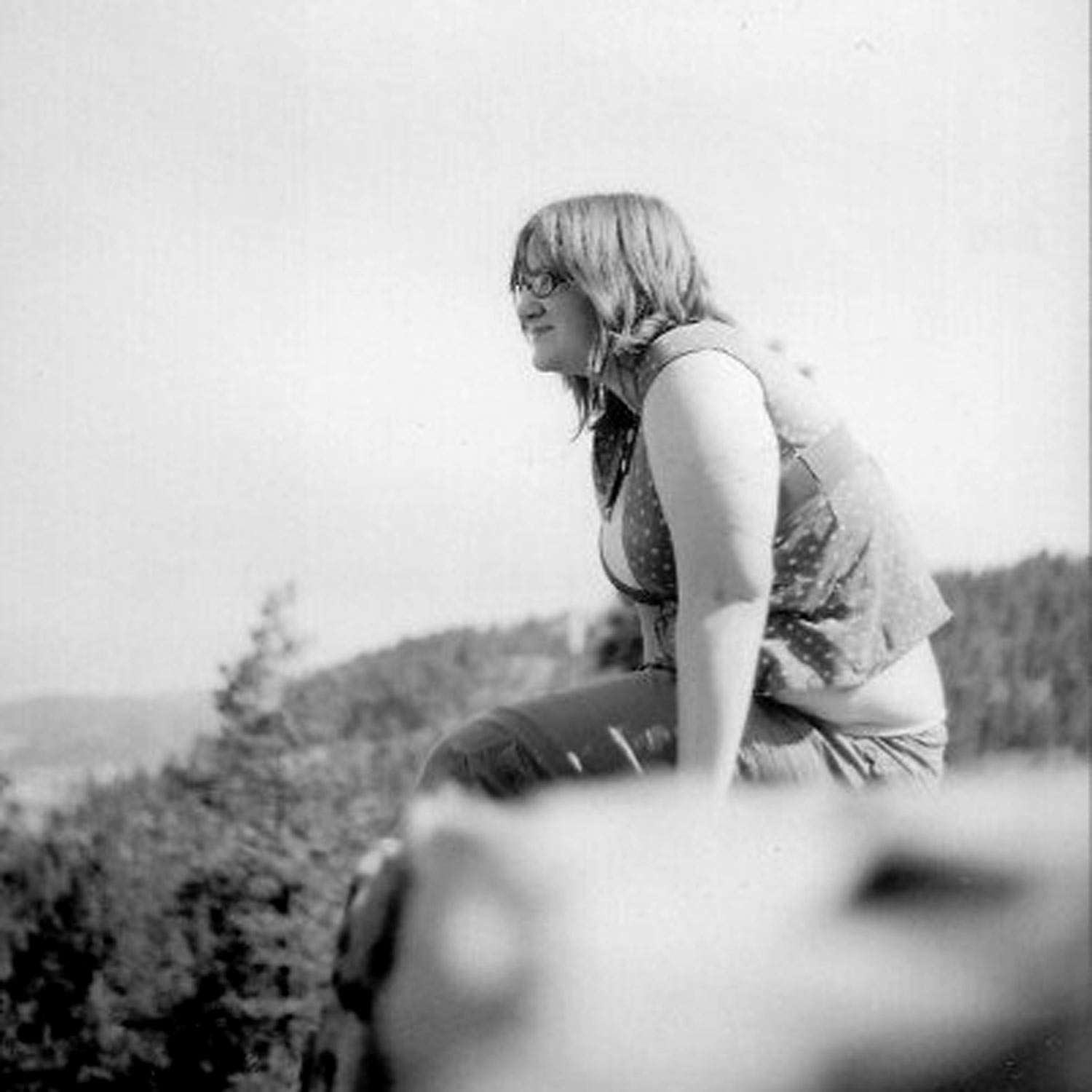

That's part of why she and HBM producer Bethany Denton were such good friends in high school. They were both fat, nearly the same size. Both tried and failed to lose weight since childhood. Together they felt safe to enjoy food without judgment.

But they parted ways after high school. Bethany moved to Washington State and Erin to Indiana for college. They fell out of touch, observing each others’ lives mostly through the distance of a Facebook news feed.

And there, Bethany began to notice changes in Erin. She looked thinner, but also more hollow. Her eyes sank into her head. Bethany was ashamed that she felt jealous. She also thought her old friend might be gone...turned into a shrinking shadow of her former self.

On this episode of Here Be Monsters, Erin explains how she developed her obsession with exercise and her intense desire to lose weight. She explains how she descended into a dangerous place with her eating disorder. She would later understand her symptoms of anxiety, insomnia and irrationality to be typical of starvation, as observed in a 1940s experiment known as the Minnesota Starvation Experiment.

After losing over 100 lbs, Erin hit rock bottom the summer after graduating from college. Her anxiety became intolerable, she was constipated, and her hair was falling out. After months of living with every characteristic of anorexia nervosa, she was given an official diagnosis once she became underweight.

"I felt like a shell...I felt so hollow."

In 2014, Erin sought treatment. The first step in her recovery was a process called refeeding. It's the process of replenishing a calorie deficit, providing a starving body much-needed energy to repair internal damage.

Erin has since made nearly a full recovery. Today she lives in Portland, Oregon and works at a bakery. She keeps a blog about her experiences with anorexia.

If you are suffering from an eating disorder, you can get help today. A good place to start is Eating Disorder Hope. Erin also recommends the website Performing Woman; she personally found it inspiring to her recovery.

This episode was produced by Bethany Denton, and edited with help from Jeff Emtman and Nick White.

Music: The Black Spot, Serocell

Bethany (left) and Erin (right) as teenagers.